Introducing Perpetual Motion

Yanbei works in long series. His paintings are always experimental variations within certain lines of research. For Yanbei there is no room for isolated and absolute works. Each unit belongs to a set and the purpose of each work comes from the connection it establishes with the whole, from the position it occupies within a series. Like a point on a line segment.

Yanbei knows the essence of painting. Fruit of his training, and his vast artistic experience, he masters the techniques and resources of traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting. The different types of strokes, the movements of the arm and the brush, the body and the shades of the China ink, the nuances of the color spots, the specifics of the support, the way the fibers of the paper absorb, transform and spread the watery colors, all this is familiar to him. Starting from this solid foundation, Yanbei explores everything that painting can offer as painting, as a medium, in an evolutionary process of self-awareness as an artist and as a person. Over and over again, he experiments, combines, modifies, superimposes, adds, withdraws, interpolates, counters, reconciles, rejects. And then starts again. He knows the possibilities are endless, that there’s no room for repetition.

This exhibition brings us a selection of works created over the last seven years. Paintings made after the major individual exhibition presented at the Macao Scientific and Cultural Centre (CCCM), in late 2018, including several works made during the period of confinement caused by the coronavirus pandemic, and also some works produced earlier this year. The selected pieces belong to three different series.

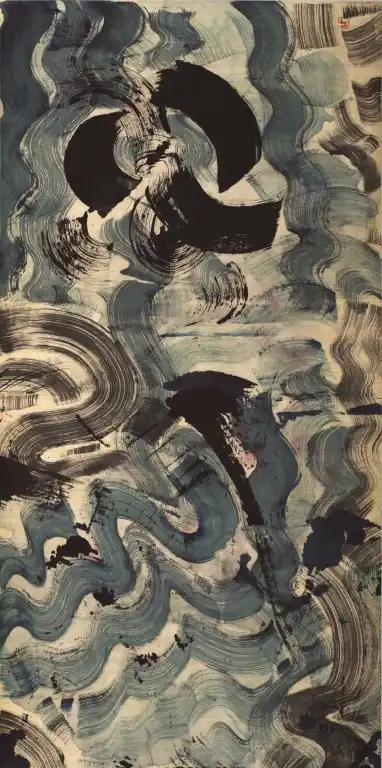

In the most representative series of this exhibition, developed between 2020 and 2024, stand out the paintings made with large black brushstrokes launched on colored backgrounds. Entangled on themselves, in serpentine movements, these brushstrokes generate spirals, concentric patterns and meanders. Despite their enlarged dimensions, the brushstrokes flow in a regular gesture, to the rhythm of a serene breath, sometimes denser, sometimes softer. Several signs recorded on the support allow to reconstruct the movement of the arm and feel the flow that accompanies it. The painter’s gesture always begins where the load of paint is strongest. The brush stroke glides on a regular slalom, in black SS, until extinguishing its ink load, being able to be “higher” or “lower”, thicker or more diluted. At the end of the process, each brush filament proves its existence through fine parallel, undulating lines inscribed on the paper. Lines that echo each other. To the black of the Chinese ink, the predominant tone, some inventive chromatic experiments are added, highlighting the lightness of the ice blue and the grayish cloudiness of the potassium alum.

Four paintings in this series, created in December 2020, reinterpret a very popular theme of traditional Chinese painting. Known as The Four Noble Flowers or the Four Gentlemen (Si Junzi), the theme consists of the separate representation of the plum blossom, the orchid, the bamboo, and the chrysanthemum. The four plants symbolize the qualities expected of virtuous people: inner beauty and modesty; delicacy and elegance; righteousness and tolerance; and resilience in the face of adversity. At the same time, combining the microcosm with the macrocosm, each plant symbolizes a season of the year, respectively winter, spring, summer and autumn. Moving away from a direct mimicry of nature, the painter explores some imperceptible details to reconfigure the plants in question within the line of research he defined for the totality of the series. Denser or lighter, the broad black brushstrokes now spread over surfaces permeated by translucent, yellowish and grayish spots, always in undulating movements. From the chrysanthemum Yanbei draws the tiny, spiraled end of the petals. Enlarging and stylizing it, the painter transforms it into an arched staff, like a crozier, which he replicates in successive juxtapositions. In turn, the filaments of each stroke of these rods multiply and overlap in soft transparencies. From the plum tree arise some violet and yellow floral notes, quite explicit, but distributed sparingly in the lower part of the painting. From the orchid a series of spikes are depicted, accentuated by some brushstrokes of light, also distributed very discreetly in the painting. And only three or four leaves allude to the bamboo, which are practically imperceptible within the vast pictorial field.

In other paintings of the same series emerge some notes extracted from the traditional Chinese calligraphic and pictorial solfege. They are a kind of confrontation with the reminiscence of his youth works, when he painted picturesque views of Beijing’s traditional alleys to sell to foreign tourists. The incessant repetition of these elements, repeated in aniconic and monochromatic fragments, accentuates the sterility of gestural mechanicism. They are used by the painter to express his disenchantment with the artificiality of the skillful combination of these elements to achieve the mimicry of visible reality. Such signs can take the form of completely stylized bamboo leaves or traces employed in the composition of Chinese characters, rehearsed tens of thousands of times by the artist in the past. All these revivals are subjugated by large black brushstrokes, which in some cases cover and hide everything. The same ones that extinguish the joviality of the pink and turquoise color fields, tones that characterize some series developed by the artist previously.

In other cases, Yanbei operates on negative transparencies, reversing the rules of the game. To achieve this goal the painter uses potassium alum, a chemical that waterproofs the support and makes it difficult to absorb new layers of paint, clearing and graying the surfaces that touch it when dry. Through the action of alum brushstrokes, the background of the painting assumes itself as form, while the movement of the brush strokes loaded with this product becomes the background. As this mordant is colorless, only at the end of the process, when drying, after the seventh or eighth coat, the artist begins to see the result of his work. There is a surprise effect, a discovery, which enriches the work and makes the result unpredictable. The works Time Immersed and Colors like neon fill the screen, both from 2021, in variations of light gray and light blue, are the most eloquent examples of this exercise.

The second series presented in this exhibition is more extensive than the previous one, dating back to 2018. The starting point was a biometric recollection, a perfectly trivial episode that ended up having a profound impact on Yanbei. On a visit to the Foreigners and Borders Service (former “SEF”), in the context of obtaining his citizen’s card, the painter confronted the implications of a new identity, a new life as “Portuguese”. A whirlwind of restlessness began to stir his spirit, an unrest that increased during the projection of his fingerprints on the screen, when he was facing his own dermatoglyphs. Formed by the elevations of the skin in the pulps of the fingers, between papillary ridges and grooves, the epidermal reliefs are an infinite galaxy with its lines of convergence, deviations, flatness, discontinuities, arches, loops, bifurcations, islets, tips, and verticils. What does all this say about the essence of an individual? What relationship is there between the subject, in its singularity, and its belonging to a community of similar beings? What do small accidents mean, those insignificant details that distinguish us from each other and, at the same time, keep us in solidarity, complementing us? What is the relationship between the printed line, organic, and the painted line, produced by the artist? Each of these questions offers a multitude of paths to explore, each with its own ramifications and crossroads. However, much more powerful, and unsettling, was the question of his younger son: Does God also have fingerprints?

In some works, the reference to dermatoglyphs, or dactylograms, is obvious, especially in the smaller circular paintings of whitish background. The serpentine patterns inscribed on the support by vermiform brush strokes suggest enlarged fingerprints. In the piece Why should the world be too hasty?, painted in 2019, the brushstrokes flow from high to low, from dense to light, until they almost fade in the lower area, next to the artist’s signature. Almost imperceptible, two very thin yellow lines intersect in the middle of the piece, in frame, referring to the questioning about God and the nature of His (eventual) dactylograms.

But in this series, it is the artist who generates life and individuality. He is the Demiurge who defines the flow of the line, the flow of life, in a perpetual motion. The paintings in this series are records of this flow of vitality, such as a breath of air or the constant flow of water. Sometimes the patterns become looser, the result of more energetic and repeated movements. Compositions that depart from the suggestion of dactylograms and assume the playful content of the pictorial exercise. A kind of expanded marginal scribbles, the kind of drawing we do in moments of boredom, looking for the pleasure of these fleeting moments of abandonment of consciousness. This results in a series of records linked to the passage of time, such as tree growth rings, fossilized ammonite spirals or overlapping strata of certain semi-precious stones, generated in the depths of the earth over millions of years.

Yanbei’s working practice holds a tectonic quality. There is an absolute incompatibility between the law of gravity and the artist’s method. The surface of the paper must rest directly on the ground, close to his feet, so that the impregnation of the paint is horizontal, slower, without running-off. That is why its observation point is always zenithal. “Anyone who wants to learn how to paint a flower,” says Guo Xi (c.1020-c.1090), should “look at it from above; then all its qualities will be fully appreciated”. Yanbei always looks up-down, he does not look ahead. His paintings are built from this point of view, and it is in this perspective that they are better understood and appreciated.

Seven paintings form the third series presented in this exhibition. Produced in late 2023 these works continue to question the nature of painting, but through different paths. The starting point is the landscape paintings dedicated to the season cycle, a recurring topic in traditional Chinese painting, including the convention for representing shifting perspectives of the same landscape. However, Yanbei operates a decomposition of the fundamental elements of this pictorial genre, contrasting aqueous color fields with small calligraphic traces, always released in forest green. Distributed in perfectly delimited areas, in the interstices of large spots of color, these small traces come to life, anthropomorphize in their gregarious behavior, huddled in the same space, overlapping each other, in lively running and conviviality. Leaving a wide margin for the experience and imagination of each one, these paintings transmit positive sensations and a certain happiness. It is a joy that the painter, generous, wants to share with us.

Luís U. Afonso

April 2024